It’s still wait-and-see time for many key characteristics of the Omicron variant.

I think the fact that it’s going to cause more breakthroughs in vaccinated people, and re-infections in people with prior infections, is baked in.

The rest will take some time.

I’ve written a lot about these questions over the past years, but here’s a few reminders on new variants.

Immunity against breakthroughs/re-infections: Any day now, we’ll get lab reports about “neutralizing antibodies” against this variant from vaccinated or infected people. I’d expect a big drop—and it may sound very large because this is reported in multiples as in “20-fold drop” or “35-fold drop.” This can be a bit misleading: they can drop a lot but still be enough to neutralize or help hold off the infection.

It’s also important to remember that antibodies are the parts of the immune system that hold off the infection from taking root—the early shock troops. As I’ve written before, the immune system isn’t just a wall, but a multi-layered defense system.

The mechanisms that stave of progression to severe disease are different, as I wrote in my New York Times op-ed on the Omicron as well:

Even if current vaccines are less effective against preventing Omicron breakthrough cases, it’s reasonable to expect them to maintain a good level of protection against hospitalizations and deaths — something we’ve seen with other variants. This is because preventing breakthrough infections and blocking progression to severe disease involve different parts of the immune system. The mechanisms by which vaccines block serious illness are likely to continue working well despite some mutations. Still, we can do much better.

The parts of the immune system that work to stave off severe disease progression are able to recognize the virus in a broader way than the antibodies that see just a small part of it. An antibody evading mutation like Superman putting on glasses and fooling someone very, very nearby because they can only look at the shape of the face in that section, but someone who can step back look at whole face can recognize it’s still our mild-mannered journalist, Clark Kent!

The antibodies are those first bouncers—they come in quick, but can only see so much and are more easily fooled. The rest of the immune system, T cells, etc. come in a little later in the game once they realize something is wrong, when infection takes hold, but can step back to look, as it were, and recognize the virus anyway even if it is mutated some. That’s why vaccines (or prior infection) can still hold off on severe disease even when they are no longer as effective in preventing infections or symptoms.

What if we’re surprised and the antibody titers don’t drop much, if at all? To be honest, I’d be really surprised because we are already seeing superspreader events among the vaccinated from Omicron, and epidemiology is usually a lot more telling than lab reports on such questions.

Transmissibility is the second important question. I expect to see more clarity on that from the United Kingdom: watch especially indicators like spread among the household from the UK Health Security Agency studies. Remember, spread can be due to inherent transmissibility or just ability to re-infect people who are otherwise vaccinated or had prior infections before. (If it were spreading among immunologically naive populations, we’d also have to wait to see if it was just chance: one strain got introduced earlier than others, but I think we are past that with this: it is spreading more—but how much of what factor is playing what size role? We shall learn, in time).

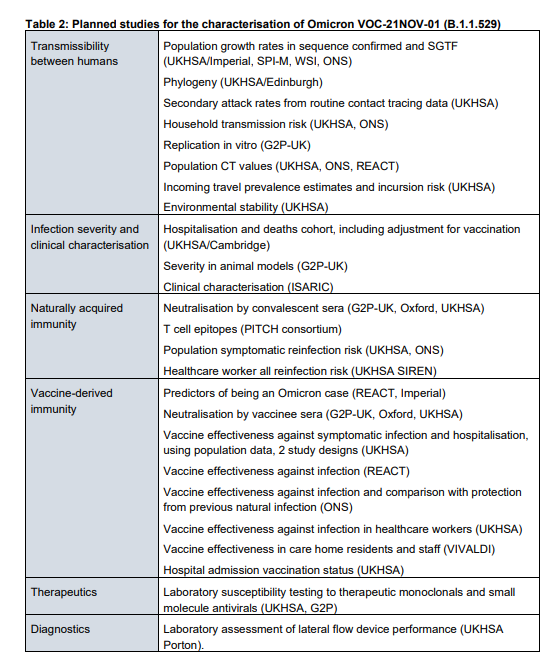

Also, for jealousy: look at all the studies the United Kingdom health agencies are doing on this, from their technical briefing on Omicron. People in countries like the United States just have to wait for others to please, do the real work it takes to understand and respond.

Severity: This remains the third and big question, in multiple parts.

First: how severe will re-infections or vaccine breakthrough will be? Immunology suggests, everything else equal, they would be milder (see this great post here, by Dylan H. Morris), but everything else is not equal. This is a new variant, and the best data on this will be the epidemiology. (There is no way to look at just the sequence and assign a disease course). Still, it is not a brand new disease for the seropositives, people with prior infection and vaccination, and one expects disease course to be, on average, milder—subject to the usual conditions like immunocompetence, age and comorbidities.

Second: what about the seronegatives? People with no vaccination, no prior infection? Well, they are already sitting ducks for Delta, which is highly transmissible and likely more severe than other strains, so the severity question may well play out differently for them. (Getting vaccinated would be the best idea, obviously).

It takes about two-three weeks from exposure and infection to hospitalization, and about four-six weeks to death, sadly. Plus, all early data is subject to selection effects: if the first superspreader events are in, say, college campuses, we get a young cohort who tend to have milder outcomes anyway, so we can’t really get a picture of severity from them easily—severe cases are already rare, so harder to tell the signal from the noise with smaller samples.

All this means it may take until the end of December or even early January to get clarity on the question of severity, likely from South Africa and United Kingdom and some European countries with good tracking.

I know this isn’t a good way to enter into the winter season, and I think even the best option will suck—many breakthroughs aren’t great to experience even if they turn out to be mild. Plus, the stress on the health system is real, plus it is winter in the Northern Hemisphere, so peak season anyway for respiratory illnesses.

By the way, getting vaccinated will certainly help even with a new variant, and so will the booster. Especially if Omicron turns out to be severe, we may be in for a variant-specific booster at some point, but the vaccines we have are still expected to provide substantial protection against severe progression, and good masks, ventilation, air-filtering etc. work against all variants.

So far, my understanding is that rapid tests will not have any issues working as before, but remember: they are good for when they are taken. Take one right before an event of consequence—not the day before.

And what if this does not turn into a crisis? That’s still possible. Still, it’s best to prepare while waiting. A few weeks of stress, and even overreaction, is better than finding out too late that it will cause us more problem than we anticipated, and also that it’s too late to do anything about it.

Let me end with the great cartoon by Jens von Bergman (deliberately in the style of XKCD):

Here’s wishing the answers we do get are as positive and hopeful as possible, but those who are planning things do not assume it before we know.

Thank you so much, Zeynep, for continuing to write this posts. They are the best source of reliable data I've seen and I appreciate your efforts to continue this conversation.

Thanks! Was waiting for your weekend read on this.