Still Not Sure Edition: Open Thread 12/19

This time, why we are still not sure.

Another Omicron open thread, unfortunately, with the same refrain: we still aren’t sure exactly how this will play out.

I think many of the worst case scenarios are off the table, but there’s still not enough clarity on some key questions and many threats remain regardless of the answers—even if they are hopeful ones.

First, let me explain why it’s so hard to be sure this time. In February and March of 2020, one could look at Wuhan and Milan and quite quickly conclude we were in deep trouble, starting likely with places like New York and London. (Which is why the lack of action deep into March was so infuriating). We were all… pretty similar. Nobody had immunity. There were no vaccines. We were all vulnerable, even if we knew outcomes varied by age and health-status, there was no reason to think any country would be truly spared—or that even youth or health was something reassuring enough to that one could turn away from the pandemic at an individual level, let alone the obvious issue: this is an infectious disease, so transmission matters. Plus, as we have all seen, many younger, healthier people have died from this (and there is also Long Covid—a topic too complicated for me to say hand-waving things about).

This time, it’s not the case. We are not all the same, globally. Yes, South Africa looks to escape the worst possible outcomes—their wave is clearly receding, without a carnage proportional to the number of cases, or hospitals being overloaded or deaths skyrocketing.

All that does give us a signal that some of the worst outcomes are off the table: this variant may be escaping our antibodies and causing infections, but it is almost certainly not escaping all of our immune system and causing severe disease or worse even in people with vaccination and or prior infection in any substantial numbers, or comparable numbers to those who are truly seronegative. That is a relief.

(The clarifications around the confusingly-handled “is it mild” question have been addressed in prior newsletters so skipping that discussion, but highly recommend this essay in the New York Times).

And yet… We still don’t know all we should because the world is no longer uniform for some of the most important variables: prior infections and vaccination.

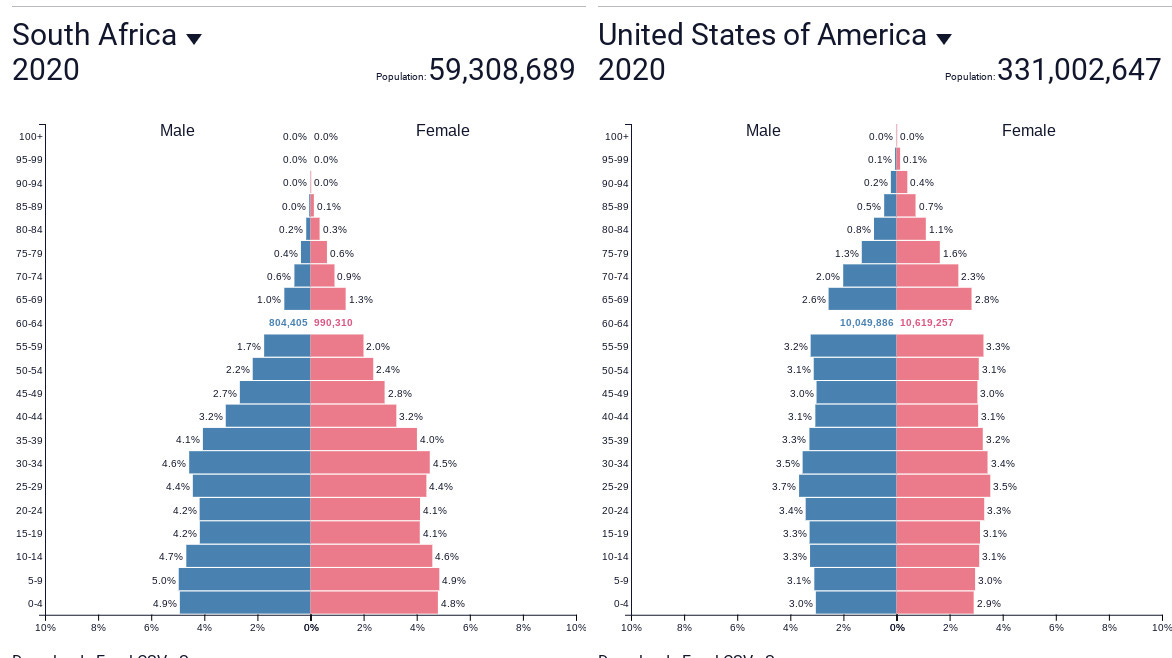

South Africa had a massive prior wave, with excess deaths of about 0.5% of the population—a staggering 250,000 for a country smaller than we are, and also much younger in age structure because so many fewer people live to older age. See this thread by Tom Moultrie, South African demographer.

And here’s the most important, sobering point:

In other words, some (unknown) portion of what happened in South Africa may well be because the worst of it had already happened there. We can’t be sure yet.

So what does this mean for us? It means we don’t really know all the answers we need just from South Africa. What will happen in breakthroughs in our elderly, for example? There is some encouraging data from there from hospitalization by age statistics, but elderly people in wealthy countries are somewhat different than ones in poorer countries—especially ones that have been devastated by the HIV epidemic for decades, and this one all through last year. Here’s our population structure, for example, compared to theirs.

Plus, not all countries have the same amount of congregate living for the elderly—nursing homes, assisted living, retirement communities. And not all of them have elderly people of similar health status, someone who reaches 75 in a rich country is not necessarily that similar to someone of the same age in a poor country, simply because the world is so unequal.

Then there are the threats from the size of the wave: if we do get some severe disease outcome from even a small percentage, this will be a big problem. Even without that, we will run out of PCR tests. (Rapid tests are already impossible to find in most places). Hospitals will lose large portions of their staff to 10-day quarantines because the staff will test positive. Already overloaded, exhausted healthcare workers can end up facing a deluge with even fewer people—and when that happens, everyone, not just those ill with COVID, will suffer. Booster appointments are being given to people into January—too late for most to help with this wave, though late is better than never. It’s back to the hustle: those with energy and time and ability to drive long distances after refreshing the pharmacy page will get boostered more than the vulnerable. And so on.

So where should we look at for what might happen to us? I think the best example, for us, so far is probably London.

Unfortunately, though, all this is happening so fast that we will soon see here, in the United States, as well. I think in New York City, we are just about a week behind London, if that.

Even under the best scenarios, a big huge wave is a big huge wave that will need managing.

Then there is the question: what about the truly seronegative? Millions of people in countries like Vietnam that have held off big outbreaks but have not completed their vaccination drive? The many countries in Africa where even health-care workers aren’t fully immunized? The remaining (dwindling) people in wealthier countries who avoided both vaccines and an infection? I don’t think we’ve hit a big enough seronegative patch yet to be sure.

Besides the lack of global uniformity, making it harder to reach firm conclusions from data from elsewhere, there is this: South African scientists notified us so early in the process that we got the warning about a month before we started getting meaningful epidemiological data from similar countries. Plus, Omicron’s spread is very, very fast—it’s clearly superspreading easily, and also transmitting very easily, which also makes it hard to figure things out fast enough.

I think the uncertainty will be much less in about a week or so—enough trendlines from the UK to start extrapolating, and some from here. But it will already be happening, and it looks like we will live through what we will live through—instead of the kind of triage and preparation this kind of wave deserved. So here we are.

As I'm sure most on here are aware, The Atlantic "Covid response team" has some good articles coming out on all things Omicron, though I their tone is coming across as more alarming than yours Zynep. It's interesting because it really reads the same in regard to general messaging.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on The Insight back to back with Omicron, we know you are busy with all of your other tasks.

I remain cautiously optimistic personally (as a bosted vax'er 46 y.o.), less so globally, but not panicked thanks to your analysis. The fast spread of Omicron does have me focused on the possibility of the next mutation. Pandemics suck, but they come and they go. Health, Strength, Luck and Joy for 2022 all.

As always, I'm deeply appreciative of Insight. Thank you.

I'd like to focus on what I think we can be sure of...

1) We, US and world, are not collecting enough data. The US could change this, especially with help from EU.

2) We, US and world, need mask education, mask production, and mask utilization. This need is independent of what we do or don't know about Omicron. Or Delta. It was true and obvious as soon as we knew Covid-19 is largely airborne.

3) We, US and world, need to rethink our approach to architecture—much as we once rethought systems for providing water and removing sewage. Air filtering, circulation, maximum access to sunlight, etc. should not be afterthoughts.

4) It looks like a qualitative improvement in anti-virals is near, or at least possible. We know that needs investigation and funding.

5) We, US and world, know not everyone will get jabs and that the vaccine itself is not enough when we consider the population as a whole and that putting all hope in vaccines has been and continues to be giving into needless deaths—especially among those who are vulnerable because of age, health, occupation, access to medical care, etc.

This note is already too long, so I will cut it here. In summary: advice to individuals in rich nations does not substitute for social and political policy on a national or international basis. We, the US, know that and we, the US, should act on that knowledge.