Our Remarkable Media Bubble: The Location Edition

The striking lack of curiosity of last year

In this newsletter, I continue to explore some of the problems that have been exposed by the way "origins" of SARS-CoV-2 are discussed and debated, rather than the topic itself.

As my New York Times article notes, the biggest reason we're discussing any of this is that the first of this pandemic outbreak detected a few miles from one of the world’s biggest coronavirus labs. There are only three that are prominent and big and, as far as I’m aware, also have done the kind of advanced bio-engineering work, such as creating chimeric viruses, that have now come under scrutiny.

There’s the one in Wuhan, China; the one in Galveston, Texas; and the one in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Any outbreak near one of them with the very virus they study would, of course, be worth noting. And I don’t mean this just for Wuhan. I have worked and lived about a mile away from the other coronavirus lab at University of North Carolina for much of the last decade. If there had been a bat coronavirus outbreak in Chapel Hill, NC, of course, we'd all be asking questions to UNC despite the fact that North America also has bats that harbor dangerous viruses.

Add the fact that the known first superspreader event (which we now know likely wasn’t where the virus originated from but just the first known amplifying event). happened at a seafood market a few hundred yards from another lab in Wuhan which also studies bat viruses, the Wuhan CDC.

Of course, even though the lab’s proximity to the outbreak is a genuinely curious fact, it is not conclusive proof by itself. One can say this without pretending the location isn’t a thing. Pandemics are rare occurrences and bring together unusual events. Outbreaks can be detected far away from their place of origin. The Marburg virus is called that because it was first detected in Marburg, a city in Hesse, Germany. even though Egyptian fruit bats — with a natural range in Uganda, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and thereabouts — are the known reservoir host for it. (The outbreak in Germany happened because workers at a biopharmaceutical plant were exposed to infected grivet monkeys from Africa). SARS was first detected in Guangdong, China, which is also far from the caves where we think it arose.

A consistent, logical and sensible discussion would note, and concede, that the location was certainly curious and unexpected, but not proof. But that discussion would also concede that repeating generalities about lab safety and zoonosis being common wasn't sufficient either by the same reasoning: pandemics are rare events that can bring together unlucky coincidences that have catastrophic consequences.

That's not what happened, though. The media coverage has been so bad, and so motivated in one direction in especially traditional liberal media, that when people suggest that the lab location is curious, they are met with the argument that there is nothing suspicious to the location simply because labs are set up where the viruses are.

Take the reaction when Jon Stewart tried to joke/talk with Stephen Colbert about the location being something that should be startling:

JON STEWART: “ ‘Oh, my God, there’s been an outbreak of chocolaty goodness near Hershey, Pa. What do you think happened?' ” Stewart said. “Like, ‘Oh I don’t know, maybe a steam shovel mated with a cocoa bean?’ Or it’s the [expletive] chocolate factory! Maybe that’s it?” .

STEPHEN COLBERT: It could be possible that they have the lab in Wuhan to study the novel coronavirus diseases. Because in Wuhan, there are a lot of novel coronavirus diseases because of the bat population there.

Stewart and Colbert may be comedians, but immediately afterwards, the Washington Post had a whole article about all this:

But if there’s one thing Stewart was often criticized for — especially by conservatives — it’s in oversimplifying complex issues to land a joke. (He often shrugged off that criticism by saying he was a comedian, not a newsman. But his show was the news to many young people, and it clearly had a political bent to it.)

And his summation of the argument for the lab leak theory suffers from some of that. Stewart pitches it as an irreconcilably massive coincidence that that virus emerged from a place with a high-level virology lab, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, that worked on novel coronaviruses.

There’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg issue, though. There’s a reason the lab in Wuhan studies viruses like the novel coronavirus; it’s because China has a history with those types of viruses emerging. As the science journal Nature summarized in a recent explainer on the lab leak theory:

Virology labs tend to specialize in the viruses around them, says Vincent Munster, a virologist at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories, a division of the National Institutes of Health, in Hamilton, Montana. The WIV specializes in coronaviruses because many have been found in and around China. Munster names other labs that focus on endemic viral diseases: influenza labs in Asia, hemorrhagic fever labs in Africa and dengue-fever labs in Latin America, for example. “Nine out of ten times, when there’s a new outbreak, you’ll find a lab that will be working on these kinds of viruses nearby,” says Munster.

Here’s one (correct) deconstruction of what’s going on in the Nature article.

It’s obvious, but saying that “coronavirus labs are found in China” (a pretty big country!) says nothing about an outbreak in Wuhan, a particular city in a big country!

Plus, as I wrote about it in my article, Chinese scientists had published about all this in the first month following the outbreak:

About a week after the lockdown [in January of 2020], Chinese scientists published a paper in The Lancet medical journal that identified bats as the likely source of the virus. The authors noted that the outbreak happened during local bat hibernation season and “no bats were sold or found at the Huanan seafood market,” so they reasoned that it may have been transmitted by an intermediary animal.

More from that Washington Post article attempting to fact-check, I suppose, Jon Stewart:

Wuhan is also extremely populous with many marketplaces, including “wet markets,” where animals who could carry such viruses are brought.

Indeed, the Wuhan Institute began studying such viruses after they were found in animals sold in those markets, as the New York Times recently reported:

That lab’s research began after another coronavirus led to the SARS epidemic in 2002. Researchers soon found relatives of that virus, called SARS-CoV, in bats, as well as civet cats, which are sold in Chinese markets. The discovery opened the eyes of scientists to all the animal coronaviruses with the potential of spilling over the species line and starting a new pandemic.

But that’s also pretty nonsensical. The lab started studying SARS because of SARS but its location is just a historic artifact, not some natural consequence of where the bat viruses are.

If anything, the lab’s location is a hindrance to this particular area of research: Wuhan scientists studying bat coronaviruses ended up doing regular trips to Yunnan—about a thousand miles away, and where SARS originated—to collect samples. In fact, Yunnan is also where they found the closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2.

Here’s a few basic “did you look it up in Wikipedia level” facts about the Wuhan Institute of Virology that I wrote in my own article:

Sometimes the curiosity around the location has been waved away with the explanation that labs are set up where viruses are. However, the Wuhan Institute of Virology has been where it is since 1956, doing research on agricultural and environmental microbiology under a different name. It was upgraded and began to focus on coronavirus research only after SARS. Wuhan is a metropolis with a larger population than New York City’s, not some rural outpost near bat caves. Dr. Shi said the December 2019 outbreak surprised her because she “never expected this kind of thing to happen in Wuhan, in central China.” When her lab needed a population with a lower likelihood of bat coronavirus exposure, they used Wuhan residents, noting that “inhabitants have a much lower likelihood of contact with bats due to its urban setting.”

Just writing this meant that I got surprised mail from people. Even such minor basic facts hadn’t made it out of the distorted media bubble of last year to the point that people were emailing me with astonishment to learn the basics about the location of the lab.

And here’s more about it, because you don’t even need to take my word for it. Here’s Dr. Shi, the leading virologist at Wuhan Institute of Virology from last July:

We have done bat virus surveillance in Hubei Province for many years, but have not found that bats in Wuhan or even the wider Hubei Province carry any coronaviruses that are closely related to SARS-CoV-2. I don't think the spillover from bats to humans occurred in Wuhan or in Hubei Province.

In other words: it’s fine to point out that pandemics are rare events and can have weird coincidences. It’s fine to point out that, obviously, an outbreak can first be detected in a city far away from its origin.

It’s also true that many outbreaks are never traced to their origin.

But the idea that there was nothing to the location shouldn’t have passed the first discerning pass, unless people were really motivated to wish it away, and shouldn’t have survived the scientific papers published in January and February of 2020 by Chinese scientists themselves.

And yet, that is where we have found ourselves, the “lab is where the viruses are, duh” becoming commonsense among people exposed to the restricted, motivated media bubble.

Just check a few examples:

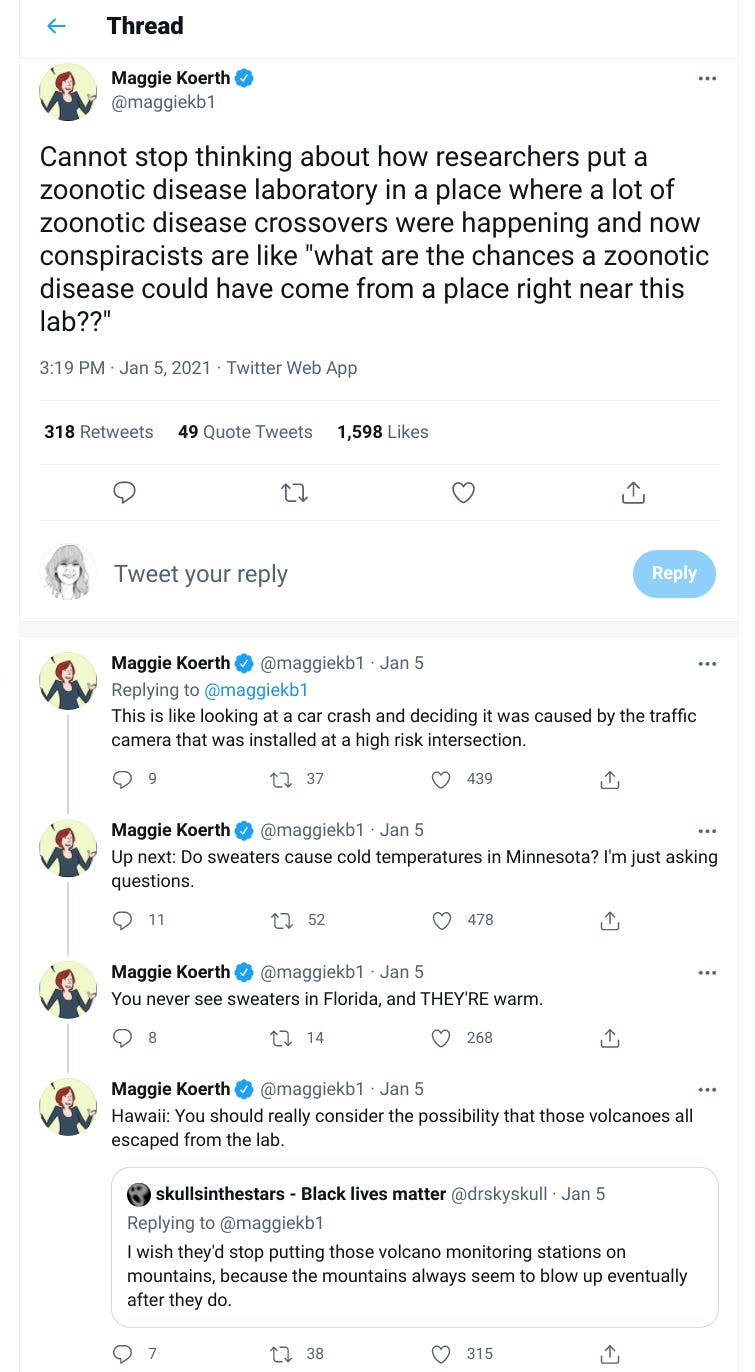

(Screenshot, because the science journalist above later said she hadn’t phrased it best, though the tweets remain up. Still, it’s remarkable that something that obviously wrong can be claimed and spread so widely, to many likes and retweets).

It’s gotten to the point that this is now “conventional wisdom” among those who rely on traditional media to follow the story (meaning people who don’t look up everything one by one themselves, and trust the general thrust of media reporting).

Even more remarkably, as far as I can tell, none of the key Chinese scientists who have published or given interviews have tried to waive away the location, ever. They admit they are surprised by the coincidence. They note that the guilty bats are far away. They say the ones in Hubei would be in hibernation, and are far from the city.

All this was just us, some of our media, scientists and journalists. With Chinese scientists and media, we can point at the repression, coercion and lack-of-freedoms that clearly restrict what they can say. (For more than a year, Chinese scientists have not been allowed to publish on the pandemic without centralized national security review. The media censorship barely requires explaining).

What’s our excuse?

This makes me think that basic Bayesian reasoning needs to be taught early. People argue as if the various factors (location, properties of previous new viruses,...) are all on different planes, so you just pick your favorite factor and ignore the others. But Bayes provides an obvious systematic way to combine different pieces of evidence, whether they point the same way or opposite ways. Most of the chances for non-lab crossover would occur elsewhere, so we can rule them out. In this case, with Wuhan having a little less than 1% of China's population and not being located in a viral hot spot, you'd take whatever odds you had based on other factors and multiple the Lab/Non-Lab odds ratio by ~100. That's not the ~infinite factor Jon Stewart seems to use but it's also not an irrelevant coincidence.

What would those other odds, not involving location, be? Some people say that there are so many more chances for nature to make new combinations that they are less than 1/100. Others say the lab was a good place for different strains to recombine, so they are more than 1/100. I don't know enough to comment on that. But including the location in the odds calculation is the easiest part to get very roughly right.

As you say, the name-calling adds nothing to the estimate!

What's our excuse? Probably the social and psychological rewards of the sneering, poorly-thought-through Twitter dunk. The platform makes it so easy and satisfying to come up with a snarky response that sounds intellectually superior, and the culture that has grown up around the platform has normalized those kinds of responses so thoroughly, that even intelligent, well-informed people like Koerth yield to temptation. I've seen it in political as well as scientific disputes; I've seen the smartest people I know retweet dunks that are easily seen, on non-confirmation-biased reflection, to not really answer the argument they're dunking on. It's more evidence that Twitter culture is undermining both our cognition and our moral sense.